|

The

idea I Capoeira I Capoeira original

I Capoeira regional I Capoeira mundial The ideaIn the beginning,

it was the idea of many to make a recording of the music of the Capoeira

with a choice of excellent musicians under optimal studio conditions. Particular

focus was to be taken of the tone-rich Berimbaus, each one

fulfilling a particular musical function, together with the percussion instruments.

Included in this project were to be the songs like the Ladainhas and

the Quadras. |

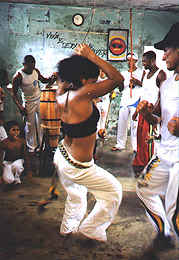

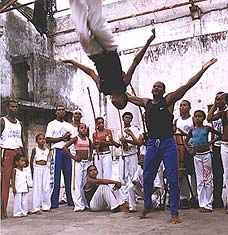

CapoeiraCapoeira

is a centuries old art form of the Afro-Brazilians. It is a form of combat

and dance, poetry and music, aesthetics and beauty, meditation and spirituality.

Piero Onori describes in his very empathetic and highly recommendable book

‘Talking Bodies´(Sprechende Körper) the essential philosophy

of the Capoeira. The key word of this philosophy ‘malicia´ can

only be roughly translated as ‘cunningness´ and ‘slyness´:"The

Capoeirista describes ‘malicia´ as the security of the animal

instinct that befriends itself with mental clarity.“ The better a person´s

‘malicia´ is developed, the better he can predict the manoeuvres

of his opponent and recognise his weaknesses. For the "Capoeira does

not rise above its members, but places them into reality.“ That´s

why a Jogo, as the dance is called, always begins upon the request

of the Mestre: E Volta pro mundo, camara! - Hey, come back into the world,

friend! Capoeira original

Capoeira regionalIn Brazil

Capoeira is a folk art, which is open to all strata of the population. It

first came as Capoeira de Angola from the Quilombos and other groups to Rio,

São Paulo, Recife and Salvador da Bahia and in the 20th century was

able to generate fulcrum points, particularly in Bahia, the spiritual sphere

of the ‘Black Rome´. Capoeira mundialThe essential characteristics of Capoeira can be recognised in the polarity, that exists between structure and improvisation, rooted in both music and dance. Further characteristics can be identified in the common ground shared with the Afro-Brazilian ritual fields and the significance of hierarchy and soloist performances on the one hand and the group pressure to conform, on the other. In instrumental play these characteristics are already in place and are very much related to the structures one encounters in jazz or rock. All of this only goes to open the Capoeira and its cultural sphere to the influences of other musicians from other cultural areas.For our album concept these encounters have proven to be even more manifold, for almost all non-Brazilian artists, no longer residing in their native countries, have already implanted themselves in the various breeding grounds of contemporary pop-music. All the invited musicians were granted complete artistic liberty, with only one restriction: the rhythm of the Toque was to be left unaltered and in return for this the original traces of the traditional Toques stored in our recording material was made available to the artists. In this way an encounter was made possible between Capoeira from the Afro-Catholic Candomblé Ritus sphere and the urban Gnawa structures represented by the Moroccan U-Cef, who now resides in London. The Gnawas are the descendants of black slaves from Mali and Guinea who were brought to Morocco. They play their music to rituals whereby spirits and demons are conjured up to for the sake of their healing powers. We will hear the riffs of the Rara-Vaccines (bamboo pipes) meet the sound of the Berimbau, much resembling the Haitian Vodou ritual, in the performances of Eval Manigat who currently lives in Montreal. Salvador was before Rio and Brazilia the first capital of Brazil. After the manumission of 1888 many Afro-Bahians came to Rio de Janeiro and formed together with their same-fated comrades from the ‘Cidade Maravilhosa´ and the refugees from the poorer north-east of the country a creative potential which Rio can now accredit for its musical trademarks like the Samba and Choro. The young Carioca Marco Schneider & Cia da Lapa has contributed his vision of a get-together between Cuica (Rio) and Berimbau (Salvador) in his Rio-City-Manguebeat. The African roots of the Capoeira are of relevance to two African musicians in completely different respects: The Senegalese Ba Mamour, now living in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, combines Capoeira with modern African vocal polyphony and Chando from Guinea Bissau, now living in Denmark, has opted for a black drums & bass version. Two young musicians from the vicinity of Bremen, Germany, under the name of Inuka have demonstrated that that even in samplings the spirit of Capoeira does not necessarily lose its tone. And for the art of improvisation with a strict playing-code, inherent to the Berimbau-Toque, there was no better choice, than the jazz musician Albert Mangelsdorff. Claus Jaeke, finally, not only filtered out the files and playbacks from our original recordings for all recordings of the Capoeira Mundial, but he also contributed to two other remixes.

O JogoUnlike Afro-Brazilian

rituals like the Candomblé the Jogo de Capoeira should not

be regarded as a means to attain other and higher levels of awareness. Gods

and spirits do not take possession of the Capoeiristas and through them appear

to serve the wishes of the community. The Mestre (in some groups also

called Capitão or Governador) is indisputably the master

of ceremonies, but he is by no means a cult chief whom all should blindly

obey. The dancers harmonise to the rhythm of the music with their body language

and can also induce changes in Toques that have been planned or begun by

the Mestre with his Berimbau. The rhythm is a mutually shared power that

is transmitted from nature via the Jogo to the benefit of all the participants. Ginga: movement in standing - in triangular form/dance-like/balancing an opponent/to and from rocking motion.(Source: Nestor Capoeira: Capoeira/Weinmann Vlg.)

The music The

berimbau is the centre of attention. Often two or more berimbaus are played

simultaneously. In such instances one musician plays the main beat (marcação

basica) and the second improvises or doubles the rhythm. In respect to

tone one distinguishes between the violinha (very high pitch), viola

(high pitch/solo) and the gunga (middle pitch) or berra-boi

(deep pitch). Berimbaus, with a particularly large calabash, are called urucucas.

The berimbau belongs to the family of musical bow instruments of African

origin. Related instruments are to be found in Angola, Cuba and Burundi.

Berbimbaus are made from rods carved from the Aracá, Gobiroba and

Biribá trees, on the upper and lower ends of which a steel string

is attached. The Mestres (who often make their own berimbaus) often fish

the strings they need out of the ash-heap that is left over from burnt, steel-belted

truck tires. Above the string and bow a hollow calabash is fastened by means

of a loop whose opening (cucumba) faces the body of the musician.

The loop´s position on the bow determines the pitch of the string,

thus dividing the pitch range into two main half-sections. The musician holds

the bow with the left hand a little above the calabash whereby the little

finger holds the loop and a coin is held between the index finger and the

thumb. The coin is pressed against the string and released again in the course

of playing. In the musician´s right hand an approximately 30cm long

stick (baqueta) is held between the thumb and index finger, with which

he strikes the string, whose tone is regulated by the coin held in the left

hand. On the right hand (usually above the small finger) hangs the caxixi,

a little wicker basket with seeds inside. Between the strikes on the string

the musician performs one or two short counter movements with the right hand

and with this action brings the caxixi into play. In the same manner that

there is a large variety African bow instruments, there are also numerous

words that equate to berimbau, e.g. urucungo, humbo or bucumbumba.

In Portuguese berimbau is another word for jews harp. The nasal-buzzing-clattering

sound of the berimbau is often likened to the human voice: the berimbau speaks

through the mouth of the calabash. Its vocal chords are the string and coin.

In the north of Brazil there are variations of the berimbau: in the berimbau-de-lata

a steel end is tautened between two tin cans and the pitch is varied by moving

the neck of a bottle in the course of striking the string. The

berimbau is the centre of attention. Often two or more berimbaus are played

simultaneously. In such instances one musician plays the main beat (marcação

basica) and the second improvises or doubles the rhythm. In respect to

tone one distinguishes between the violinha (very high pitch), viola

(high pitch/solo) and the gunga (middle pitch) or berra-boi

(deep pitch). Berimbaus, with a particularly large calabash, are called urucucas.

The berimbau belongs to the family of musical bow instruments of African

origin. Related instruments are to be found in Angola, Cuba and Burundi.

Berbimbaus are made from rods carved from the Aracá, Gobiroba and

Biribá trees, on the upper and lower ends of which a steel string

is attached. The Mestres (who often make their own berimbaus) often fish

the strings they need out of the ash-heap that is left over from burnt, steel-belted

truck tires. Above the string and bow a hollow calabash is fastened by means

of a loop whose opening (cucumba) faces the body of the musician.

The loop´s position on the bow determines the pitch of the string,

thus dividing the pitch range into two main half-sections. The musician holds

the bow with the left hand a little above the calabash whereby the little

finger holds the loop and a coin is held between the index finger and the

thumb. The coin is pressed against the string and released again in the course

of playing. In the musician´s right hand an approximately 30cm long

stick (baqueta) is held between the thumb and index finger, with which

he strikes the string, whose tone is regulated by the coin held in the left

hand. On the right hand (usually above the small finger) hangs the caxixi,

a little wicker basket with seeds inside. Between the strikes on the string

the musician performs one or two short counter movements with the right hand

and with this action brings the caxixi into play. In the same manner that

there is a large variety African bow instruments, there are also numerous

words that equate to berimbau, e.g. urucungo, humbo or bucumbumba.

In Portuguese berimbau is another word for jews harp. The nasal-buzzing-clattering

sound of the berimbau is often likened to the human voice: the berimbau speaks

through the mouth of the calabash. Its vocal chords are the string and coin.

In the north of Brazil there are variations of the berimbau: in the berimbau-de-lata

a steel end is tautened between two tin cans and the pitch is varied by moving

the neck of a bottle in the course of striking the string. Other instruments of note are the reco-reco (scraper), the chocalho (shaker), the agôgô (two-bells percussion instrument), the pandeiro (hand drum with bells) and the tamburim and the atabaques (high and deep African drums). The songs of the Jogo are Afro-Brazilian, i.e. the style of singing, intonation and alternation between choir leader and choir are of African origin while verse forms and musical idioms belie Portuguese influence. The Jogo ritual is actually an unsung one. Before the dances the ladainhas extol the descent of the Capoeiristas, the Mestres and in other respects. In the Capoeira Regional these are called quadras. Up until the beginning of the Jogo one can also hear the faster chulas. There are songs that are used to mock and irritate and it is in this respect that parallels can be found as far as Trinidad, where the Calypsoes emerged out of the spiteful songs of the stick-fight combatants around the end of the 19th century. There are many Capoeira song texts, for every toque a countless number of them. The reason for this is that they allow free space for individual embellishment and regional variation. Even recent commentaries on the event that take place in the roda can be integrated into the ritual as an object of mockery, derision or disdain.

The ToquesThe rhythms

move predominantly in 2/4 oder 4/4 beat and occasionally there is a 6/8,

like in the Cavalaria which goes to augment its intended warning function.

According to the progress being made in the Jogo the tempo can vary from

very slow to very fast. The toques presented in this compilation have found

the concurrence of all Mestres and Academias and their students. However,

sometimes the opinions on these matters do not always coincide, e.g. whether

Jogo de dentro is a toque or not, is often a matter subject to the

respective age of the Capoeirista. © 2001 by Claus Schreiner All rights reserved |

|

|

| At your local recordstore: click here for a list of our international distributors |

|

|

| Capoeira Academias, Martial Arts Schools, Websites please contact us to obtain information on reseller-discounts, links on your homepage with comissions on orders, PR-cooperation, info-rmaterial etc. | |

| Send your mail to tmrecord@t-online.de |

(top)

TOQUE

DE ANGOLA, IUNA, SAO BENTO GRANDE, SAO BENTO PEQUENO; SANTA MARIA, JOGO DE

DENTRO, CAPOEIRA REGIONAL, CAVALARIA

TOQUE

DE ANGOLA, IUNA, SAO BENTO GRANDE, SAO BENTO PEQUENO; SANTA MARIA, JOGO DE

DENTRO, CAPOEIRA REGIONAL, CAVALARIA

There is

no solid proof that Capoeira found its way directly from Africa to Brazil.

It´s, however, worth having a look in the Congo/Angola region to search

for possible traces of its origin. Musicians from Brazil and Angola can indeed

combine Angolan Sembas and Brazilian Samba into a common song,

they cannot, however, play or dance any Capoeira together, for a counterpart

cannot be found in the whole of Africa. Proof of Angolan origin can be certainly

found in the Berimbau and the drums. The verses sung between the solo-singers

and choir belie a relationship to a key word, ‘Batuque´

(Portuguese: Umbigada), which appears to be an extant souvenir of the Bantu

culture of the Congo region, representing a typical schemata of the African

dances that were imported into eastern Latin America, between Cuba and Montevideo,

with the slaves: a circle comprising of musicians, singers and choir singers

and a hand-clapping audience is formed, in the middle of which one performs

a solo dance or competes with another, until one signals, by touching another

person on the hip, that it is his/her turn now. In Brazil this principle

has been incorporated into the Samba and innumerable forms of Afro-Brazilian

folklore and the scenic folk plays.

There is

no solid proof that Capoeira found its way directly from Africa to Brazil.

It´s, however, worth having a look in the Congo/Angola region to search

for possible traces of its origin. Musicians from Brazil and Angola can indeed

combine Angolan Sembas and Brazilian Samba into a common song,

they cannot, however, play or dance any Capoeira together, for a counterpart

cannot be found in the whole of Africa. Proof of Angolan origin can be certainly

found in the Berimbau and the drums. The verses sung between the solo-singers

and choir belie a relationship to a key word, ‘Batuque´

(Portuguese: Umbigada), which appears to be an extant souvenir of the Bantu

culture of the Congo region, representing a typical schemata of the African

dances that were imported into eastern Latin America, between Cuba and Montevideo,

with the slaves: a circle comprising of musicians, singers and choir singers

and a hand-clapping audience is formed, in the middle of which one performs

a solo dance or competes with another, until one signals, by touching another

person on the hip, that it is his/her turn now. In Brazil this principle

has been incorporated into the Samba and innumerable forms of Afro-Brazilian

folklore and the scenic folk plays. According

to the chronicles Capoeira appeared for the first time in Brazil after the

largest settlement and centre of resistance (Quilombo) for escaped

slaves, Palmares, had fallen in 1695 with the murder of their leader

Zumbi, after almost 100 years fighting against the Dutch and the Portuguese

colonialists. Zumbi, like his predecessor Ganga-Zumba, was a member of the

Nago (Bantu/Angola) Africans, and Capoeira, it is believed, either emerged

as a rediscovery of old African traditions in Palmares or was developed as

a technique of combat. For a long time Capoeira was carried out in rough

manner, even with knives - in times when dancing was used more to camouflage

events of a more violent nature and where in some regions of Brazil rogues

and bandits were imprecated as ‘Capoeiro´. The authorities made

heavy weather of this popular sport, which remained attached to the Quilombos,

illegal secret secret societies and other forms of popular resistance. Many

of the events of this time are recorded in the chronicles, some of the recordings

taking the form of pictorial representation: between 1816 and 1831 a drawing

made by the Frenchman Debret appeared showing two musicians with Berimbau

and Balafon (Mbira) and the artist Rugendas drew in 1824 Capoeiristas

with clenched fists without a Berimbau.

According

to the chronicles Capoeira appeared for the first time in Brazil after the

largest settlement and centre of resistance (Quilombo) for escaped

slaves, Palmares, had fallen in 1695 with the murder of their leader

Zumbi, after almost 100 years fighting against the Dutch and the Portuguese

colonialists. Zumbi, like his predecessor Ganga-Zumba, was a member of the

Nago (Bantu/Angola) Africans, and Capoeira, it is believed, either emerged

as a rediscovery of old African traditions in Palmares or was developed as

a technique of combat. For a long time Capoeira was carried out in rough

manner, even with knives - in times when dancing was used more to camouflage

events of a more violent nature and where in some regions of Brazil rogues

and bandits were imprecated as ‘Capoeiro´. The authorities made

heavy weather of this popular sport, which remained attached to the Quilombos,

illegal secret secret societies and other forms of popular resistance. Many

of the events of this time are recorded in the chronicles, some of the recordings

taking the form of pictorial representation: between 1816 and 1831 a drawing

made by the Frenchman Debret appeared showing two musicians with Berimbau

and Balafon (Mbira) and the artist Rugendas drew in 1824 Capoeiristas

with clenched fists without a Berimbau.  Despite

the changeable positions taken by the authorities further Capoeira institutes

were, in the course of time, being (officially) opened and meanwhile a city

like Salvador da Bahia has gained further significance on account of the

Capoeira. It offers children and youths places to learn and become involved

in Capoeira as a measure to combat the insurmountable problem of street children.

But this is like many of the other projects inaugurated by the Brazilian

government, ‘here today, gone tomorrow´, and there is already

a myriad of internet sites calling for international solidarity for a Capoeira

Academia in Salvador that are due to be cut off from official sponsorship

and closed. Bahia´s great writer Jorge Amado referred to Mestre Pastinha

as one of the greatest figures in Bahia´s public life. And nevertheless,

the almost blind Pastinha had to in 1973 leave his house, situated in the

historical district, Pelourinho, because of a planned redevelopment

project and close his Academia (Capoeira de Angola), which was founded in

1941. Other famous Mestres from Salvador are Mestre Waldemar, Mestre Caicara

and Mestre Ezikiel.

Despite

the changeable positions taken by the authorities further Capoeira institutes

were, in the course of time, being (officially) opened and meanwhile a city

like Salvador da Bahia has gained further significance on account of the

Capoeira. It offers children and youths places to learn and become involved

in Capoeira as a measure to combat the insurmountable problem of street children.

But this is like many of the other projects inaugurated by the Brazilian

government, ‘here today, gone tomorrow´, and there is already

a myriad of internet sites calling for international solidarity for a Capoeira

Academia in Salvador that are due to be cut off from official sponsorship

and closed. Bahia´s great writer Jorge Amado referred to Mestre Pastinha

as one of the greatest figures in Bahia´s public life. And nevertheless,

the almost blind Pastinha had to in 1973 leave his house, situated in the

historical district, Pelourinho, because of a planned redevelopment

project and close his Academia (Capoeira de Angola), which was founded in

1941. Other famous Mestres from Salvador are Mestre Waldemar, Mestre Caicara

and Mestre Ezikiel. In

Rio Mestre Bimba came into contact with Asian martial arts, elements of which

he incorporated into his Capoeira in order to make it more attractive for

the youth, for he received official permission for his Academia and other

projects because he committed himself to the Edução Fisicia

(physical education) of the youth. Mestre Bimba enjoyed great popularity,

even beyond Brazil´s borders. His playing style, called Capoeira

Regional, is often offered as an alternative to the Capoeira de Angola,

particularly outside of Bahia. Compared to the ‘Angola´ style

the Capoeira Regional is more combat orientated, more open to new influences

and in every respect more modern.

In

Rio Mestre Bimba came into contact with Asian martial arts, elements of which

he incorporated into his Capoeira in order to make it more attractive for

the youth, for he received official permission for his Academia and other

projects because he committed himself to the Edução Fisicia

(physical education) of the youth. Mestre Bimba enjoyed great popularity,

even beyond Brazil´s borders. His playing style, called Capoeira

Regional, is often offered as an alternative to the Capoeira de Angola,

particularly outside of Bahia. Compared to the ‘Angola´ style

the Capoeira Regional is more combat orientated, more open to new influences

and in every respect more modern.